Continuing Education Activity

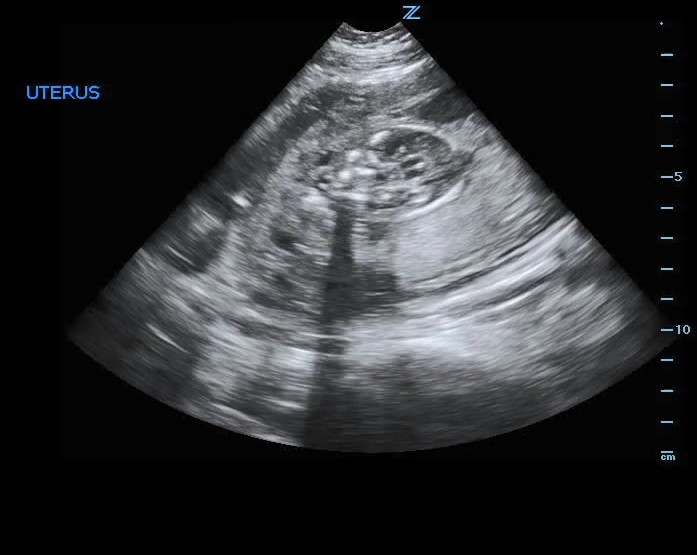

During the third trimester of pregnancy, ultrasound is commonly performed in patients that present both asymptomatically or with symptoms. There are currently no major guidelines or protocols to standardize the use of ultrasound at this stage of pregnancy. Ultrasound can be useful to identify fetal and maternal pathology and to follow the progression of the pregnancy. This activity reviews the approach and interpretation of ultrasound during the third trimester and highlights relevant information for an interprofessional team managing this patient population.

Objectives:

- Describe the general technique to perform an ultrasound evaluation during the third trimester of pregnancy.

- Identify the indications and contraindications for performing an ultrasound evaluation during the third trimester of pregnancy.

- Describe the typical fetal and maternal ultrasonographic findings during the third trimester of pregnancy.

- Summarize the most common pathologic findings that can be appreciated when performing an ultrasound evaluation during the third trimester of pregnancy.

Introduction

The use of ultrasound in the third trimester of pregnancy serves a multitude of general and specialized purposes that include but are not limited to the determination of fetal number and presentation, assessment of growth disorders, and characterization of the placenta and amniotic fluid. Thus, the ultrasonographic applications in the third trimester of pregnancy differ from previous trimesters in both scope and objectives.

Traditionally, the third trimester is defined as the antenatal period between 28 and 42 weeks of gestation. There is currently no universal, standardized protocol for assessing the progression and status of the pregnancy during this period.

Sonographic assessments in the third trimester are not routinely performed unless the patient has had no initial sonographic examination or prior pathological or concerning conditions are identified during the first or second trimesters.[1]

The purpose of the study serves as a guide for what is evaluated during the examination. Further detailed studies about abnormal findings are described more extensively under their respective activities.

Anatomy and Physiology

During the third trimester, ultrasound can be performed transvaginally or trans-abdominally, with preference given to the latter approach due to the theoretical risk of precipitating clinically significant hemorrhage if placenta preview is present and undiagnosed.[2] The transvaginal approach generally offers better visualization of the anatomy due to the improved proximity to the organs and structures of interest. However, due to the higher frequency transducer used, this can result in difficulty visualizing more caudal (maternal) and deeper structures inside and outside the uterus.

The uterus is typically found wedged between the more anterior bladder and the more posterior colon. In a cephalad to caudal direction, the fundus, body, and cervix of the uterus can be appreciated in that particular order. During the third trimester, the fetal anatomy and cardiac activity should be well defined and evident.

The amniotic fluid should be seen as an anechoic space surrounded by the isoechoic walls of the uterus. The location of the placenta is variable, and it can be identified as a heterogeneous structure connected to the wall of the uterus and attached to the umbilical cord leading to the abdomen of the fetus.[3]

Indications

In an asymptomatic, gravid female, third-trimester ultrasound is indicated for the evaluation and determination of:[1]

- Fetal anatomy

- Fetal anomalies

- Gestational age

- Fetal growth

- Fetal presentation

- Suspected multiple gestations

- Placental location

- Cervical insufficiency

Third-trimester ultrasound examination on the symptomatic pregnant patient has multiple indications, including, but not limited to, the following conditions:[1]

- The discrepancy between the uterine size and calculated gestational date

- Pelvic mass

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Fetal death

- Fetal anomaly

- Vaginal bleeding

- Abdominal or pelvic pain

- Hydatidiform mole

- Uterine abnormalities

- Fetal abnormalities

- Amniotic fluid abnormalities

- Placental abruption

- Premature rupture of membranes

- Premature labor

- Placenta previa

Additionally, other applications of ultrasonography include acting as an adjunct to procedures, e.g., amniocentesis, cervical cerclage placement, external cephalic version.

A particular patient population that is especially benefited from using ultrasound in the third trimester is the late presenter without prior prenatal care. Unfortunately, these patients are prone to all aforementioned disorders, and an ultrasonographic evaluation is of paramount importance to avoid, or at least plan for, significant morbidity and mortality causes.

A more detailed and specialized examination of fetal anatomy and characteristics of the placenta may be required under certain clinical circumstances.[4] These protocols and applications are beyond the scope of the objectives of this chapter.

Contraindications

There are few contraindications for the use of transabdominal ultrasound during the third trimester of pregnancy. The only universally accepted absolute contraindication is patient refusal, following the principle of patient autonomy.

Transvaginal ultrasound is relatively contraindicated during the third trimester, especially in patients without a prior documented placental location, due to concerns for precipitating bleeding in the setting of undiagnosed placenta previa. It is recommended to begin with a transabdominal ultrasound to locate the placenta first, followed by the transvaginal ultrasound if clinically indicated and necessary. However, due to the cervix and the vaginal canal angle, performing transvaginal ultrasound during the third trimester can be potentially safe. The risk of precipitating clinically significant hemorrhage has not been consistently supported in the literature.[5]

Equipment

For appropriate sonographic evaluation, two probe transducers must be available. A curvilinear probe (1 to 6 MHz) is the preferred probe for transabdominal assessment, while a high-frequency endocavitary probe (7.5 to 10 MHz) is used for transvaginal evaluation.

A probe cover must be used for the transvaginal approach. After each use, the probe should be appropriately disinfected as per institution protocols.

Preparation

If performing a transabdominal study, the patient should be asked to have a full bladder if possible as fluid-filled structures enhance the resolution of deeper structures on ultrasound as it aids in examining the uterus, placenta, and amniotic fluid.

If a transvaginal ultrasound is deemed necessary, the patient should be asked to empty their bladder. Given the proximity of the intracavitary probe to the cervix, an empty bladder provides increased visualization of structures and improves patient comfort during the study.[6]

Technique or Treatment

The initial evaluation should commence by placing a curvilinear probe with the appropriately selected OB settings over the suprapubic area. The probe can be placed in either sagittal or transverse orientation. The probe indicator should be directed to the cephalad for the sagittal images and towards the patient's right side for transverse images.

If a transvaginal examination is indicated, the patient should be placed in the lithotomy position. The probe should be inserted with the indicator in the vertical direction. Sagittal images are obtained by maintaining the indicator pointing towards the ceiling, while transverse imaging requires rotating the probe to have the indicator facing the patient's right side.[4]

Several measurements are indicated for appropriate assessment of the status of the fetus and the maternal structures, starting with the estimation of the gestational age. Gestation dating by ultrasonography may be inaccurate during the third trimester.[7] Measurements of fetal parts can be used in isolation or combined to estimate gestational age. Commonly used dating measurements include:

- Biparietal diameter (BPD)

- Occipitofrontal diameter (OFD)

- Head circumference (HC)

- Abdominal diameter (AD)

- Abdominal circumference (AC)

- Femur length (FL)

On the other hand, estimation of fetal size is best performed during the third trimester.[8] Multiple formulas have been developed to estimate fetal weight, with one of the most widely used being that of Hadlock and colleagues. Formulas that used less than three fetal body part measurements did not perform well compared to formulas that include fetal head, abdomen, and femur measurements.[9] However, including additional measurements in the formulas has not demonstrated increased accuracy.[10]

Frequently, fetal movement can be identified and should be documented. However, lack of fetal movement can have different significances and can be affected by the fetal sleep cycle. The fetal heart should be measured using M mode as established by As Low As Reasonably Achievable (ALARA) recommendations.[11] The M mode caliper should be placed over the left ventricle. By measuring the temporal distance in M mode from peak to peak, most modern ultrasound machines will be able to estimate the fetal heart rate. Care must be applied to the correct number of cycles measured since some manufacturers will require two cycles to be measured, and some only one. A normal heart rate is between 110 and 160 beats per minute. Further discussion about abnormal findings is discussed below.

Evaluating the fetal lie is of paramount importance, especially as the term date approaches. First, the fetal head is identified, followed by the direction of the hyperechoic fetal spine. If the fetal head is closer to the cervix, this is described as cephalad. The laterality of the spine is also essential, and it is always described based on the mother's orientation. On the other hand, when the head is more cephalad to the mother, it is considered a breech presentation. The specific type of breech presentation should be evaluated as frank, complete, or footling.[12]

The fetal anatomy should be evaluated for any apparent abnormalities. The laterality of all anatomic structures visualized should be noted. The fetal head and its general should be examined for symmetry. Intracranial anatomical structures should be visible, including the cerebellum, cavum septum pellucidum, and ventricles. The inability to identify any of these structures warrants further investigation.[13]

The probe should be optimized to assess the heart's movement, position, and orientation in detail. During the third trimester, the four heart chambers should be visible. The fetal heart rate should be evaluated for any signs of arrhythmia. The lungs should be seen flanking the heart bilaterally, and they should appear echogenic and homogeneous, in what is described as "liver-like."[14]

Further moving caudally in the fetus, the abdominal organs should be appreciated. The stomach is seen on the left side as an anechoic cystic structure below the diaphragm.[15] Bilaterally, the kidneys should present symmetrically, and the bladder should be seen in the inferior abdomen as a small hypoechoic cystic structure.[16] From the anterior abdominal wall, the insertion of the umbilical cord should be evaluated for any sign of extrusion of intrabdominal organs. Finally, the long bones and the spine should be followed and assessed for symmetry. The spine should be symmetric, hyperechoic, and should taper to an intact posterior skin edge.[17] The position, movement, and tone of the extremities should also be examined.

A general evaluation of the cervix is wise. First, by visual inspection, the sonographer should determine if the cervix is open or closed. If open, the distance from the inner wall to the inner wall should be measured. Subsequently, due to the morbidity associated with cervical insufficiency, the length from the outer to the inner cervical os should also be measured.[18]

The placenta can be identified by tracing the endometrium until an isoechoic structure with increased vascularity on color Doppler. The location of the placenta should be described as anterior or posterior. The location of the placenta should be described as anterior or posterior. The presence of placenta previa should be excluded by measuring the distance from the caudal edge of the placenta to the inner cervical os. A measurement of less than 3 cm is concerning for placenta previa and should be further evaluated.[19]

The placenta should be further inspected for masses or retroplacental hemorrhage, which will appear as heterogenous or anechoic areas, respectively. Its size in both longitudinal and transverse axes should be determined. Any abnormal finding should be further studied by applying both Color Doppler and Power Doppler modes.

From the placenta, the point of insertion of the umbilical cord should be traced and classified as central, eccentric, marginal, or velamentous. After applying color Doppler mode to the umbilical cord, both venous and arterial flow pulsations should be distinguished. Ideally, spectral doppler should be seen in the free cord, but this can be technically challenging at times. In these cases, consistency should be preferred over accuracy, and it should be measured at a site where it can be reliably reproduced. Once a continuous wave Doppler is applied, an umbilical artery waveform following a “sawtooth” pattern should be easily discerned from the venous flow. A resistive index can be calculated by applying the formula as follows:

resistive index (RI) (Pourcelot index) = (peak systolic velocity – end-diastolic velocity) / peak systolic velocity

Doppler indices are known to decline with the progression of the gestational age, given that diastolic flow increases gradually. If the umbilical artery resistive index is abnormal, further investigation is warranted.[20]

Finally, the amniotic fluid level should be measured by both amniotic fluid index (AFI) and deepest vertical pocket (DVP) methods if possible. To assess AFI, using the linea nigra and mediolateral lines as the axial and horizontal axis, the sonographer must divide the uterus into four different quadrants.

The deepest pocket identified in each quadrant devoid of both fetal parts and the umbilical cord is measured vertically. The dimensions in centimeters of these measurements are added together to calculate the AFI. Normal AFI is between 5 to 25 cm. An AFI of less than 5 cm is considered oligohydramnios.[21]

To determine DVP, the deepest pocket of fluid devoid of fetal parts and the umbilical cord is identified and measured vertically. A value of less than 2 cm is concerning for oligohydramnios, while more than 8 cm indicates polyhydramnios.[22]

As stated before, abnormal findings required further specialized sonographic examination and prompt consultation with an obstetrician. Other specialized studies fall beyond the scope of this activity.

Complications

The most significant risk of complication can result from a transvaginal ultrasound approach that can disrupt the integrity of a placenta previa, leading to iatrogenic hemorrhage. Due to the angle of orientation between the placement of the endocavitary probe and the position of the cervix, some studies have argued that this risk is potentially overstated. However, there are no major risks associated with the alternative of using a transabdominal approach to the evaluation of the gestation during the third trimester, so this should be preferred and attempted first.

Other minor risks associated with the use of ultrasound entail the anxiety that it can elicit on the patient and the discomfort associated with the pressure of the probe against the skin or vaginal mucosa.[23]

Clinical Significance

The initial component of the ultrasonographic evaluation should be the determination of the number of fetuses. There is an increased risk of morbidity and mortality associated with unexpected multiple gestations. Common errors that can lead to misidentification of the correct plurality include not performing a full scan, including the uterus's fundus, or not tracking the fetal head continuously to its corresponding body.[24]

Subsequently, once a fetus is identified, viability should be assessed by evaluating cardiac motion and fetal heart. Fetal heart rate also provides additional prognostic value. A slow fetal heart rate has been associated with a poorer prognosis, but this should not be the sole determination to consider the pregnancy nonviable.[25]

Fetal lie and presentation are of higher importance in the third trimester than the first and second trimester. Change in these two parameters decreased as the due date approaches. Fetal lie refers to the angle of alignment of the fetus and uterus in the sagittal axis. Longitudinal lie, the most commonly found, refers to both the fetal and uterine axis aligning in parallel. The other two possibilities include a transverse, and less commonly, an oblique lie.[12]

Presentation, on the other hand, refers to the fetal anatomic part closer to the cervix. The cephalic position is the most commonly found with the fetal head as the presenting part, and it correlates with improved delivery outcomes. Malpresentation, including breech, footling, or kneeling, is often associated with increased labor difficulty and, consequently, with increased morbidity and mortality. Ultrasound can determine both complete and incomplete variations of presentation. Both fetal lie and presentation must be assessed concurrently since an incomplete examination can misinterpret the findings. If the fetal head is closer to the cervix or lower segment of the uterus, the fetal lie in the sagittal axis should be confirmed before reporting a cephalic presentation since the fetus could be in a transverse axis. If a malpresentation is identified, the ultrasonographer should assess and evaluate potential causes, including placental abnormalities or fetal malformations.[26]

Estimating gestational age and weight should be attempted with the caveat that measurements in the third trimester are less accurate than those made during the first trimester. Fetal abnormalities can also affect the measurements of different body parts.

An important aspect of the examination in the third trimester is the evaluation of the amniotic fluid. There remains some controversy about the best methodology when there are moderate abnormalities in fluid volume, but more concordance exists at the extremes. The initial evaluation should subjectively allow for assessment for polyhydramnios and oligohydramnios. It is important to remember that near-term, amniotic fluid volume may appear decreased due to the relatively larger size of the fetus. Objective measurements should follow either using the deepest vertical pocket method (DVP) or amniotic fluid index (AFI). A diagnosis of oligohydramnios should prompt emergent referral and assessment by an obstetrician due to the associated prognosis of fetal demise. On the other hand, polyhydramnios requires a less emergent consultation but should prompt further evaluation and testing since it can be associated with complications for the mother and the fetus. In the case of multiple gestations, an increased amniotic fluid volume must raise immediate suspicion for an etiology related to a fetal abnormality. The majority of cases are related to twin to twin transfusion syndrome.[27]

Determining the location of the placenta and its relation to the cervix is a critical aspect of the examination. If performing a transabdominal ultrasound examination, various maneuvers can correctly assess the placenta, including changing patient position. If this fails, a transvaginal exam can be considered. If the diagnosis of placenta previa cannot be excluded despite all efforts, one must be cautious and assume the presence of the diagnosis. In patients with prior cesarean section in which a placenta previa is identified, further detail should be directed towards assessing for placenta accreta.[28]

In patients that present for abdominal pain, a significant concern is a placental abruption. However, ultrasound is not ideal for identifying placental abruption as both false positives, and false negatives are common. The myometrium and its supplying vasculature can frequently be mistaken for a hematoma. On the other hand, a small abruption can be easily confused for normal myometrium.[29]

Ultrasonography also offers the opportunity to evaluate the umbilical cord and determine the presence of vasa previa. Findings that should raise suspicion for this diagnosis include resolved placenta previa, succenturiate placental lobe, and velamentous cord insertion.[28]

A commonly asked question during the ultrasonographic examination is the presence of fetal abnormalities. It is impractical to examine every patient for every possible abnormality. However, major abnormalities are usually evident on a routine examination. Determining what is considered reassuring in the absence of any obvious abnormality remains debated, given the complexity of the issue. Furthermore, abnormalities detected during the first and second trimester of pregnancy can disappear in the third trimester. Opposite to that, some abnormalities only become apparent with the advancement of gestation. It is currently recommended that if only one ultrasound is performed, that it should be done at 18 to 20 weeks of gestation. Any malformation found should be further evaluated by a sonographer with expertise in the precise abnormality discovered.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The approach to taking care of the pregnant patient during the third trimester of pregnancy requires an interdisciplinary effort involving physicians, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, and other healthcare team members. There are multiple factors to consider during this period, and ultrasound has evolved as an essential tool to evaluate the progression of pregnancy. Even though there is no universal recommendation to obtain a routine ultrasound in the third trimester, its use can help identify pathology that can directly affect the outcome of both the patient and the pregnancy. Understanding the applications and limitations of this tool can help reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Ultrasound examination at the bedside and performed by an experienced provider should be considered in all pregnant patients present during the third trimester. Patients who have not received prenatal care benefit greatly from its use as undiagnosed pathology can be identified. The function of ultrasound during this period is to identify pathology that could have been missed as well as to determine factors that directly affect the delivery, e.g., fetal lie, fetal size, fetal presentation, placental location. The ultrasound examination must be thorough and yet focused. Its completion includes an examination of the fetus, placenta, amniotic fluid, umbilical cord, and cervix.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

An important advantage of the ultrasound examination is its reproducibility. Repeat examinations can be performed if dynamic changes are suspected. Additionally, patients with identified pathology should receive a specialized examination that is beyond the scope of this article. Nursing should be prepared and familiar with the terminology of ultrasound findings to monitor and provide assistance in the delivery of patients with pathology.