Anatomy and Physiology

Several anatomical and physiological concepts are essential to comprehend the various techniques of myocardial protection fully. One of the cardinal concepts was arresting. The heart was supporting the need for energy while maintaining cellular integrity. This achieves the two goals of a bloodless still field and avoids air embolism risks upon opening the heart's left side. This concept was the pillar of creating the first cardioplegic solution. The idea was administering a high potassium concentration solution directly into the coronaries to arrest the heart.[2][3]

Original physiological foundation concepts of myocardial protection

- (Nernst Equation – Action potential – Electrolyte composition)

The exact interaction between potassium and the myocyte action potential was extremely crucial in developing cardioplegia and its evolution. Walther Hermann Nernst in 1881 created Nernst's equation that enables us to calculate the equilibrium potential (in this case resting potential) of any given membrane (the myocyte membrane) given the concentration of any ion (in this case electrolyte K) on both sides of the membrane. The equation is

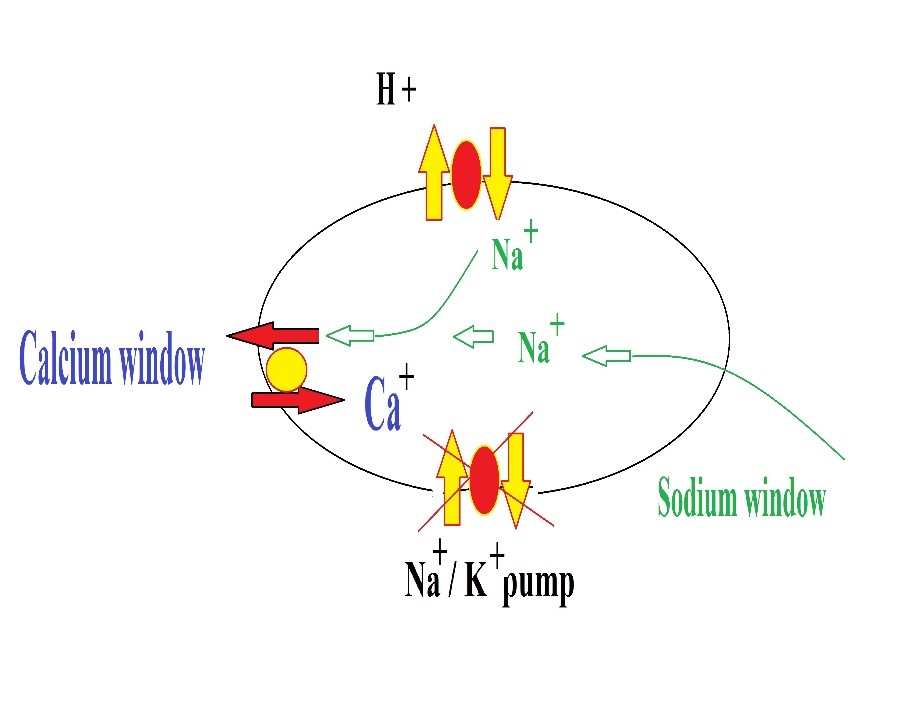

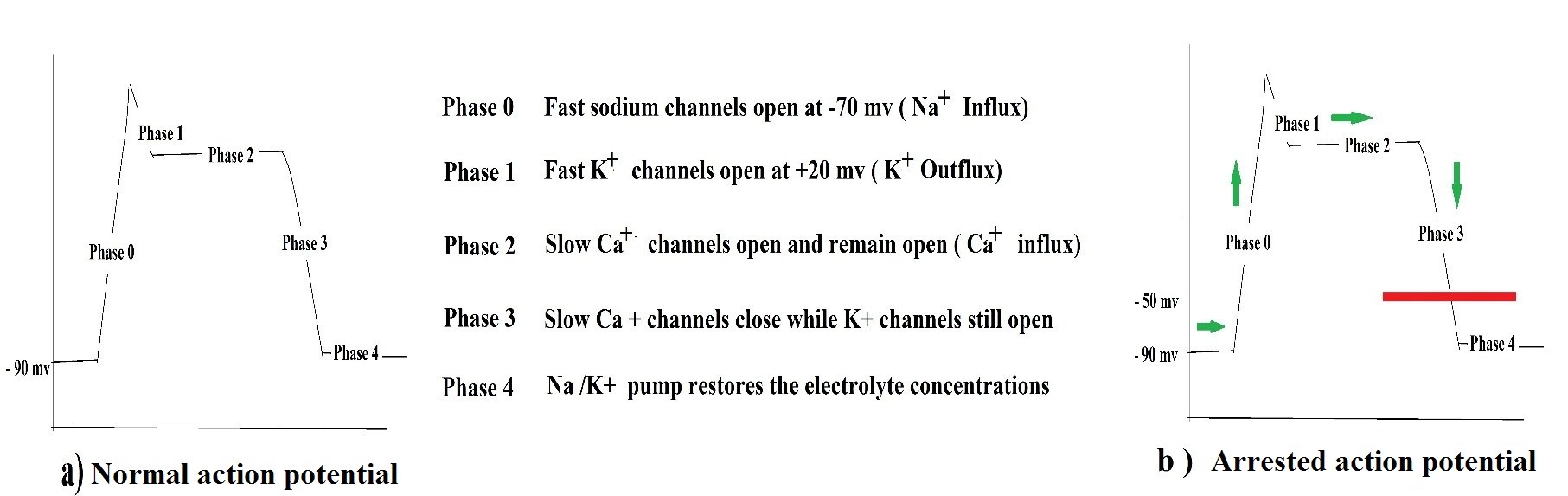

Where E is the resting potential, C is the concentration of K outside the membrane, and C is the concentration of K inside. If potassium outside is typically 4 mmol / L, the resting membrane is naturally – 90 mV. If potassium increases to 20 mmol/ L, this makes the resting potential -50 mv. But how will this lead to the arrest of the heart action potential? Fig 1. The idea essentially relies on the extracellular fluid around the myocyte. If it gets displaced by a cardioplegic solution of a potassium concentration 20 mmol/L instead of the usual 4 mmol/ L, the myocyte becomes "trapped" in a state of resting membrane potential of – 50 mv, which prevents phase 0 from initiating since sodium channels need a threshold of – 70 mv to open. This threshold potential is not achievable as long as the extracellular potassium is 20 mmol rather than 4 mmol as per the Nernst equation. The composition of extracellular and Intracellular fluids accordingly plays a significant role in the action of cardioplegia Table 2

|

|

Potassium

|

Sodium

|

Calcium

|

|

Intracellular

|

144 mmol /L

|

10-15 mmol /L

|

≤ 1 mmol / L

|

|

Extracellular

|

4 mmol/L

|

144 mmol/L

|

4 mmol

|

Table 2 Electrolyte concentrations

More recent concepts of myocardial protection:

(Calcium load/paradox – Oxygen consumption – Elements of protection)

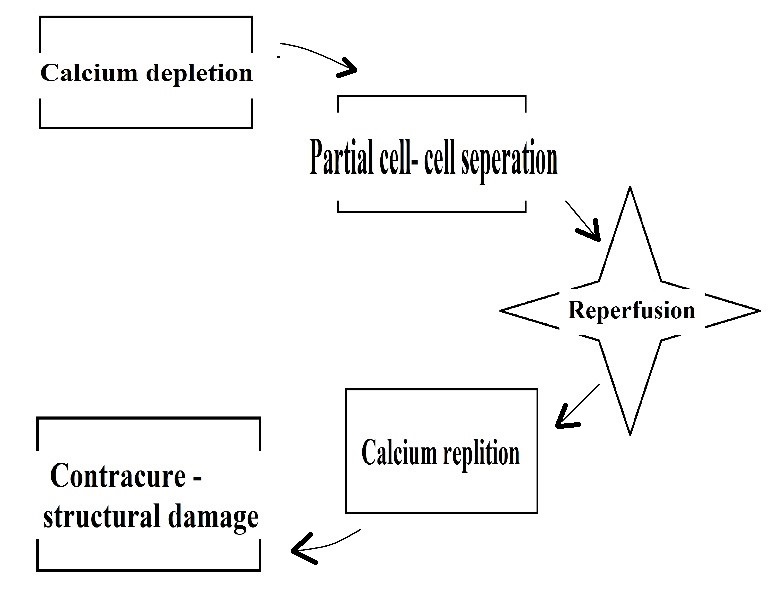

It was noticed that the histological changes found after only 30 and 60 minutes of ischemia/reperfusion were comparable to the degree of necrosis generally seen after 24 hours of permanent coronary occlusion. Researchers accordingly concluded that there must be effects for reperfusion just as equal to ischemia, and the term ischemia-reperfusion injury then evolved. Unfortunately, this is beyond this paper's scope, yet we mention two of the elements of I/R injury relevant to our topic here. That is calcium overload and calcium paradox. Upon using the first cardioplegic solution, a series of observational studies reported abnormal heart failure, intractable fibrillation, and widespread necrosis. One of the mechanisms proposed for this damage was calcium overload. The idea is summarized in Fig2. Calcium free solutions were then proposed. However, these also showed a similar phenomenon upon reperfusion with physiological calcium levels. This phenomenon was referred to as the calcium paradox, multiple theories were postulated, and one of the widely accepted theories is illustrated in Figure 3. It is essential to mention that the observation of effects preceded the full understanding of the mechanisms.

It was evident that any cardioplegic solution imposes some damage along with its protective effect. To solve this dilemma, researchers launched a careful examination of the elements of protection and injury. One of these critical studies was the oxygen consumption of the myocardium. In a series of experimental studies, Follette et al. and Gerald D. Buckberg described the O2 consumption of the myocardium and compared it in normal hearts, beating decompressed hearts on CPB, fibrillating hearts, and electromechanically arrested hearts Table 3

|

|

37 C

|

32 C

|

28C

|

22 C

|

|

Beating empty heart (CPB)

|

6 mL

|

5 mL

|

4 mL

|

3 mL

|

|

Fibrillating heart

|

6.5 mL

|

4 mL

|

3 mL

|

2 mL

|

|

Arrested heart

|

1 mL

|

< 1 ml

|

0.5 mL

|

< 0.5 mL

|

|

Normal heart uses 10 mL/ 100 g / min

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3: Myocardial oxygen consumption in beating empty heart, fibrillating heart, and arrested heart

Lots of information was deducted from this study. The factor that produces the most reduction in myocardial oxygen consumption is electromechanical arrest regardless of the temperature. The heart in the fibrillating state effectively reduces oxygen consumption than the decompressed beating heart except at normothermia.

Hearse DJ, in his book published in 1981 titled 'protection of ischemic myocardium: cardioplegia, 'described the elements of myocardial protection in detail. Hearse divided the protection into three main items. 1) electromechanical arrest 2) hypothermia 3) additive protective factors to counteract the deleterious effects of the solution used and hypothermia. Magnesium citrate to counteract calcium overload, THAM /HCO to counteract acidosis, mannitol/albumin to counteract cellular edema, local anesthetics such as procaine to counteract membrane instability, and amino acids/glucose counteract reduced energy substrates and nutrient stores, for instance.

Anatomical Concepts of Myocardial Protection

The anatomy of coronary circulation and venous drainage of the heart is also essential in understanding the rationale behind myocardial protection strategies. For instance, studies have shown that retrograde cardioplegia alone is suboptimal in protecting the right ventricle because tributaries of the coronary sinus are poorly distributed among the right ventricular muscle mass, and venous drainage of the right ventricle involves the use of Thebesian veins more frequently. Using retrograde cardioplegia in severe proximal coronary artery disease has proven more effective in protecting the left ventricle because of the more widespread distribution of coronary sinus tributaries. It enables the cardioplegic solution to reach beyond the obstruction points.

Technique or Treatment

Techniques of Myocardial Protection

When Bigelow or Melrose proposed arresting the heart in order be able to operate under direct vision, they were aware that if they are going to interrupt the coronary circulation using a cross-clamp, they must find a way to protect the heart (hence the term myocardial protection) and the body (in particular the brain, cerebral protection). Two-thirds of the answer was already provided by developing cardiopulmonary bypass machines, which maintained systemic circulation, decompressed the heart, and reduced its work and oxygen consumption. They had to find the final third of the answer. Bigelow suggested hypothermia, whereas Melrose suggested cardioplegia, and along the line, non-cardioplegic techniques then developed.

All the techniques mentioned above are considered myocardial protection methods, so the word myocardial protection and cardioplegia are not synonymous, contrary to common mistakes. All techniques evolved with time; Bigelow's concept, for instance, founded the basis of 'deep hypothermic arrest 'used today. Melrose technique founded the basis for all cardioplegic techniques developing afterward. Non-cardioplegic techniques as a result of a temporary setback of cardioplegic techniques. Cardioplegia composition and delivery methods went through various stages. Every time a particular composition and delivery mode was implemented, certain defects were revealed. This led to the study of a new composition and delivery model; however, the old defects were replaced by new ones. Ultimately none of the techniques was abandoned entirely.

Of course, some techniques became more popular than others, such as blood cardioplegia compared to crystalloid cardioplegia or extracellular compared to intracellular cardioplegic solutions. Some techniques also became associated with certain conditions/situations, such as retrograde cardioplegia delivery in severe aortic regurgitation or tight proximal coronary stenosis. No single technique replaced the others altogether. The following is a review of the techniques in more or less chronological order of their evolution.

Cardioplegic vs. Non-cardioplegic Techniques

Initially, 2.5% potassium citrate cardioplegic solution was used after decompressing the heart using the heart-lung machine. It was infused into the aortic root until a full arrest is achieved, and excess was avoided. No fixed quantity was specified. The safe period of arrest was 30 minutes, after which re-dosing is mandatory. Reperfusion at the end, then with blood, calcium chloride, adrenaline, neostigmine, and the cardiac massage was done. In none of the cases, the heart failed to arrest nor fail to recover. However, almost unconditionally, all hearts showed ventricular fibrillation, and electric defibrillation was used. Researchers started to observe intractable fibrillation, poor contractility, and myocardial necrosis. Many theories were postulated regarding the poor outcomes; some attributed it to citrate, others attributed it to the reperfusion method, but all agreed to abandon it. This continued for 15 years, during which non-cardioplegic techniques prevailed, three main techniques were described.

Surgeons operated under one of three conditions 1) perfused beating heart using continuous coronary perfusion either antegrade initially described by E.B. Kay, H.T Bahnson, J.B Littlefield or retrograde utilized by Lillehei CW, Gott VL and this method was mainly for aortic valve surgeries. Obvious problems were cumbersome set-up, possible injury to coronary ostia, and being limited to valvular heart surgery, especially aortic valve, made it less favored. 2) Topically cooled heart introduced by Shumway and colleagues, which was suitable for all acquired heart disease surgery and proved good results in the long run; however, it had the limitation of alleged physical injury to the heart. Also, Debate upon the safe ischemic time was ongoing. 3) ischemic arrest using intermittent aortic occlusion in which the surgeon cross-clamps the aorta at room temperature. This was considered the most popular because it was the most unadorned, most straightforward, and least demanding technique. However, a prerequisite for using the anoxic techniques (2,3) was a 'fast operator' as per Robicsek F.[5] These techniques continued to be used until the famous paper by Cooley DA describing the phenomenon of intractable widespread myocardial contracture post anoxic arrest referred to as " stone heart."[6] This restarted the cardioplegic era again, looking this time for a better cardioplegia solution to replace Melrose's solution.

Although subsequent experimental studies perfected the cardioplegic techniques, yet non-cardioplegic techniques re-surfaced again. For instance, surgeons use continuous coronary perfusion during aortic root surgery or sometimes omit cross-clamp and induce fibrillation (referred to as fibrillatory arrest) in porcelain aorta cases. Intermittent aortic occlusion regained popularity after studies on 'Ischemic preconditioning.'

Extracellular vs. Intracellular Crystalloid Cardioplegia

Simultaneous to Cooley's description of the stone heart phenomenon, several advances in the field of cardiac investigations led to a better understanding of the status of the myocardium post-open-heart surgery. Also, in the United States, UCLA's breakthrough research on microspheres enabled us to accurately quantify the myocardium's perfusion. This revealed that non-cardioplegic techniques are far from being ideal, especially in high risk and prolonged operative time cases; this revived the search for an alternative cardioplegic solution.

A solution containing sodium concentration is equivalent to intracellular fluid 10 to 15 mmol/L (hence the name intracellular crystalloid cardioplegic solution). This leads to the failure of action potential to initiate from the start, i.e., phase 0 fails to initiate Fig 1. In other words, the myocyte fails to depolarise. Instead, the myocyte remains hyperpolarised (hence the name hyperpolarising crystalloid cardioplegic solution). This provides several benefits, making it a safer solution 1) no calcium release at phase two of the action potential prevents the calcium load phenomenon and its subsequent deleterious effects. 2) avoids high potassium concentration, which is a chemical irritant and can only be used in small quantities repeatedly, interrupting surgery flow.

On the other hand, the hyponatremic solution is not equally irritant, which allows its administration in a more considerable amount once or twice without interrupting the flow of surgery for re-dosing. Despite these benefits, the hyponatremic solution (Brettschneider solution) was not free of faults. One of the major problems noted was the calcium paradox phenomenon Brettschneider.[7]

Colleagues worked on the formula several times before producing the final version containing histidine, tryptophan, glutamate, and calcium trace ions on top of the previously mentioned components. Histidine is a temperature-dependent buffer that maintains PH at 7.40 when the solution's temperature is 4 C. In London, David Hearse and Mark Bainbridge started working on a different cardioplegic solution. They concluded that the amount of potassium in the first cardioplegic solution was too much, around 200 mmol/ L, and all that needed was 20 mmol/L, i.e., it was previously 10-fold in excess. They then proposed a solution with sodium concentration resembling the extracellular fluid with the addition of 20 mmol/L potassium (hence the name extracellular cardioplegic solution).

The mode of delivery was cold antegrade. In the case of intracellular solutions, this was to promote histidine action, which works only at 4 C. But regardless of this detail, cold cardiac surgery was the consensus since Bigelow proposed it. At this stage, no extensive studies were looking into changing the mode of delivery. It was yet to come in the development of cardioplegia.

Blood vs. Crystalloid Cardioplegia

In the USA, Dr. Buckberg and colleagues were at the summit of understanding the deleterious effects of non-cardioplegic techniques, particularly normothermic intermittent aortic occlusion. They studied all means to enhance subendocardial flow and reduce the incidence of ventricular fibrillation post-cross-clamp removal. Buckberg and colleagues proposed certain maneuvers, including limiting hemodilution, venting, adequate perfusion pressures, decreasing hypothermia in addition to perfusate resuscitation. They called it 'the integrated ischemic technique. Their recognition that the blood cardioplegic solution could resuscitate the heart made them realize that they should substitute blood for the cardioplegic vehicle's crystalloid portion. Numerous benefits of blood were described by various authors, including improved microvascular flow due to rheologic effects. The idea is that coronaries are better adapted to carry blood as compared to crystalloid solutions. This allowed improved cardioplegia distribution beyond the stenosis. Also, it reduces hemodilution, myocardial edema due to its content of plasma proteins. Blood also has endogenous scavengers for oxygen-free radicals. Blood shows higher acid-base buffering capacities than any synthetic buffers. Other advantages include its content of hemoglobin, which has better oxygen delivery properties.

Blood contains glucose, amino acids, fatty acids, and other minerals and nutrients, allowing better myocardium recovery. Various experimental and clinical studies proved the superiority of blood cardioplegia. Multiple surveys showed that blood cardioplegia has exceedingly become the favored technique by most surgeons both in the UK and USA.[8][9]

The question changed from being: shall we use blood cardioplegia? How should we deliver blood cardioplegia? Various surgeons use various combinations to deliver cardioplegia. However, certain situations favor particular delivery systems over others. Understanding the pros and cons of various systems enables the surgeon to select the ideal system in various situations properly.

Warm vs. Cold

The first part of the question to be answered was the temperature. Initially, the preferred temperature to deliver blood cardioplegia was 36 C, i.e., normothermia. This was merely the natural progress of events. As we explained above, blood cardioplegia was an evolution of the resuscitation solution used by Buckberg and colleagues to enhance recovery of the myocardium post removal of cross-clamp. Studies were then split upon the answer, initially favoring warm blood cardioplegia followed by others who favored cold blood cardioplegia and knowledge of the oxygen dissociation curve (fig 4).' This was proved correct in vitro by several researchers who proved that in the arrested heart, the reduction in oxygen consumption is minimal at lower temperatures and almost negligible below a temperature of 20 C (see table 2).[10][11] This was also proven correct by other researchers. Also, the deleterious effects of hypothermia were described extensively in numerous studies. Some of these effects include Na - K adenosine triphosphatase inhibition, reduced energy substrates, cellular edema, reduced nutrient stores, and reduced homeostatic abilities. Also, hypothermia leads to calcium sequestration, increased CO production, and subsequent acidosis.

Moreover, hypothermia causes sludging and rouleaux formation, which reduces the delivery of a cardioplegic solution to myocardial tissues.[12] Those in favor of cold blood cardioplegia came later to prove that hemoglobin's oxygen delivery abilities are not affected, simply because myocardial acidosis and hypercarbia during arrest counteracts hypothermic effects and cancels the oxygen dissociation curve left-hand shift and, in some instances, even shift it to the right.[13] The other deleterious effects of hypothermia claimed to be theoretical simply because certain additives are naturally present in the blood, such as magnesium counteracts calcium sequestration, buffers control hypercarbia acidosis, nutrients counteract the reduction in energy production, plasma proteins counteract cellular edema. Also, close control of hematocrit during cardiopulmonary bypass using hemofiltration limits the sludging and rouleaux formation.[14]

The addition of procaine counteracts membrane instability. So actually, there is no damage caused by using cold blood cardioplegia, but is there a benefit? Yes, is the answer. Studies have shown that cold blood cardioplegia is better in restoring baseline myocardial functions, particularly after prolonged aortic cross-clamping.[15][16] Multiple surveys showed that most surgeons in the UK and USA prefer cold blood over warm blood cardioplegia.

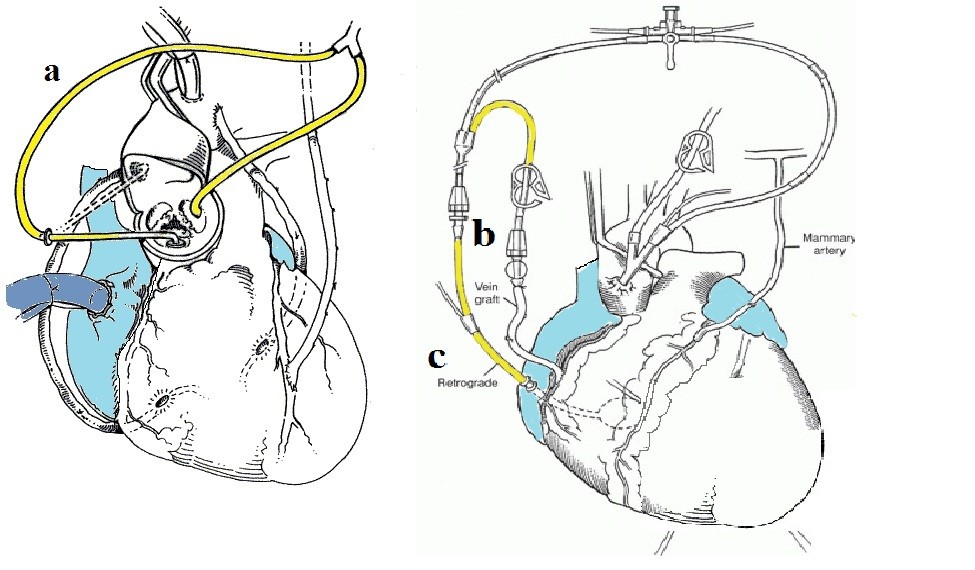

Continuous vs. Intermittent

The development of cardioplegic techniques leads to more complex surgeries being feasible. Cross-clamp times gradually increased over time. This unmasked some flaws in the technique. In particular, the problem was evident with long cross-clamp times above 120 minutes. As usual, the scientific society started looking into past techniques that faded with time in a trial to reproduce it more practically and overcome problems associated with long cross-clamp times. Such as continuous coronary perfusion. It was one of the non-cardioplegic techniques that emerged after the failure of the Melrose technique. The idea was instead of protecting the heart during the 'downtime' by reducing its requirements via electromechanical arrest and hypothermia, the heart was protected via continuous perfusion with normothermic cardioplegic solution. In other words, rather than 'decreasing demand, increase supply.' The term 'warm heart surgery' or ' aerobic heart surgery' evolved. Three ways of continuous cardioplegia delivery are described in Fig 4.[17]

Depending on the type of surgery, one of the three methods is used. The proposed benefits were. First, cross-clamp time will no longer matter. Also, hypothermia is no longer required. Other benefits include the better reach of cardioplegia beyond stenotic coronary lesions, a better wash of metabolites, more uniform perfusion of the myocardium, reducing the incidence of subendocardial necrosis, and overcoming the collateral coronary flow coming from pericardial vessels and coronary veins that washes out cardioplegia.[18][19]

Several authors nevertheless challenged the concept. Philippe Menasche (French pioneer of retrograde cardioplegia) published a famous editorial titled " Warm cardioplegia or aerobic cardioplegia, let's call a spade a spade." His point was, all surgeons utilizing continuous cardioplegia had to interrupt, giving it for variable periods due to obscuring the field.[20] During this pause, the myocardium is in an anoxic state, but this time without hypothermia protection. So, according to Menasche, the continuous/aerobic technique is neither continuous nor aerobic. With the evolution of the ischemic preconditioning concept, these brief episodes were found to be, in fact, beneficial.

Cessation of cardioplegia delivery for up to 15 minutes while doing the distal anastomosis was found to improve lactate washout abilities of the myocardium post-reperfusion, which lead to the evolution of the famous Calafiore technique in 1995. Again, no final verdict regarding the optimal mode of delivery was reached. Surveys showed a discrepancy in practice between the UK and USA; continuous infusion was used more in the USA. It is worth mentioning that certain situations favor continuous infusion over intermittent such as aortic root surgery, complex pediatric surgeries, combined surgeries, or redo surgeries. It is instrumental in complex operations to avoid stopping now and then for cardioplegia re-dosing, interrupting surgery's flow, and may significantly prolong clamp time. In aortic surgeries, having the aorta widely open, sometimes provided sufficient size/space, it becomes easier to fix soft cardioplegia cannulas to the coronary ostia and give cardioplegia without interrupting the flow of surgery.

Antegrade vs. Retrograde

With laboratory techniques, researchers could obtain much information about the myocardial condition during cardiopulmonary bypass. Such techniques include microspheres research that enabled accurate quantification of myocardial perfusion, also coronary effluent flow studies that enabled measurement of myocardial oxygen requirements. The development of animal models that resemble ischemic hearts enabled numerous testing concepts such as arterial grafts, ischemic preconditioning, and ischemia-reperfusion injury.

One of the concepts that were challenged was the route of cardioplegia. Originally it was antegrade. No particular reason; it was common sense and mimicked physiology. Retrograde cardioplegia was the evolution of retrograde coronary perfusion, which was utilized among other non-cardioplegic techniques (see before).[21][22][21] Of course, these were two completely unrelated techniques. Yet, the idea of being able to insert a cannula into the coronary sinus and infusing blood continuously through it in the late 50s inspired Menasche in the 80s to use the same route. Only this time, he infused a cardioplegic solution. Menasche was also inspired by a series of clinical studies that highlighted antegrade cardioplegia defective protection in the presence of critical coronary stenosis. The idea was obvious; critical stenosis limits the amount of cardioplegia reaching the myocardium.

Clinical studies also showed a severe issue with antegrade cardioplegia in aortic valve replacements. Which is the inadvertent coronary ostial damage during the administration of plegic solution? Menasche was enlightened by experimental studies that showed the superiority of retrograde cardioplegia in protecting the left ventricle in the presence of critical coronary stenosis.[23][24]

The technique was not free of flaws. In particular coronary sinus, injuries were a concern for which multiple remedies were proposed, including right atrial cardioplegia, proposed by Carpentier, or pulsatile retrograde cardioplegia proposed by Okike co-workers.[25][26][25] The biggest concern was, the right ventricle was reported to be less protected by several authors. Although others, including Menasche himself, challenged this, it remained a concern until now. Menasche blamed the catheter balloon for the delayed recovery of the right ventricle. Initially, a small Foley catheter was used to deliver cardioplegia, the balloon of which was spherical and bulky, which, according to Menasche, obstructed the terminal 0.5 cm of the sinus before the right atrium. This terminal part drained most of the right ventricle and the inferior interventricular septum. Hence, he reverted to a specially designed cannula with a discoid balloon. In the USA, Dr. Gerald Buckberg proposed routine use of a combination of antegrade and retrograde cardioplegia. He titled it 'the integrated myocardial protection technique,' shown in surveys favored by many USA surgeons. Surveys, however, showed antegrade cardioplegia more commonly used in the UK.

There are certain situations, however, that favor using retrograde; these include; critical coronary stenosis, aortic regurgitation in non-aortic surgeries, heavy calcifications occluding coronary ostia in aortic surgeries, or if continuous cardioplegia is to be used (see before).

Diluted vs. Microplegia

Since Dr. Gerald Buckberg proposed blood cardioplegia, the routine was a 4 to 1 ratio of blood to the cardioplegic solution. This mixture was compliant with the commercially available solution concentrations and tubing size used in cardiopulmonary bypass machines. Hemodilution per se had its benefits; in particular, it reduces rouleau formation and improves microvascular flow. In 1996 Dr. Menasche, in collaboration with Dr. Calafiore, proposed limiting the additives and adding them directly into the bloodstream almost with no dilution. This had several benefits, including increasing the hemoglobin concentration, subsequently increasing oxygen delivery. Also, reducing the hemodilution effect of cardiopulmonary bypass. Also, this technique proved to be more cost-effective. Recently, an automated pump was developed.[27]