Continuing Education Activity

Pellucid marginal corneal degeneration is a progressive peripheral corneal thinning disorder with an adjoining area of ectasia above it. It is a relatively rare ocular condition and usually occurs in males in the 2nd to 5th decades. To avoid ocular morbidity and permanent visual loss associated with this condition, it must be promptly diagnosed and treated. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of pellucid marginal corneal degeneration and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Explain the etiology of pellucid marginal corneal degeneration.

- Describe the appropriate evaluation of pellucid marginal corneal degeneration.

- Outline the treatment modalities for patients with pellucid marginal corneal degeneration.

- Summarize the importance of collaboration and communication amongst the interprofessional team to enhance the care for patients with pellucid marginal corneal degeneration.

Introduction

Pellucid marginal corneal degeneration (PMCD) is a bilateral, noninflammatory, peripheral corneal thinning disease. It is characterized by a peripheral crescentic band of thinning, usually in the inferior cornea. The ectatic zone, which is 1-2 mm from the limbus, lies above the point of the maximum corneal thinning. The term pellucid marginal degeneration was coined first by Schalaeppi in 1957 as "la dystrophie marginale inferieure pellucide de la cornee". "Pellucid," meaning clear, signifies the clarity of the cornea despite the presence of ectasia.[1]

The condition is more common in males in their 2nd to 5th decades of life. It is very important to rule out any thinning and ectatic disorders like keratoconus and PMCD before refractive surgery as upon being missed, they can lead to unwanted complications post-operatively.

Etiology

The etiology of PMCD is largely unknown. Similar to keratoconus, electron microscopy of the cornea in PMCD reveals abnormally spaced collagen fibers with a periodicity of 100 nm to 110 nm, as opposed to 60 nm to 64 nm found in normal corneas.[2]

Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea have been associated with PMCD in the literature. The repeated occurrence of hypoxic conditions in these patients may be hypothesized to lead to anaerobic glycolysis and stromal acidosis, and in turn, promote transcription of proinflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-alpha or interleukin-6, leading to corneal thinning.[3] Also, floppy eyelid syndrome found in obese patients may lead to chronic mechanical rubbing of the cornea leading to thinning and ectasia.

Atopic and vernal keratoconjunctivitis has been linked in reports to superior PMCD. Coexistent retinitis pigmentosa, chronic open-angle glaucoma, scleroderma, retinal lattice degeneration, eczema, and hyperthyroidism have been observed in some patients with PMCD, but no direct causative association has been found to be true.[4][5][6][5][4]

Epidemiology

Many authors have proposed that PMCD could be just a peripheral form of keratoconus.[7] Thus the exact incidence of PMCD is expected to be underestimated. The general consensus is that PMCD is a rare condition. It has been seen to be more common in males and affects all ethnicities with no geographical predisposition.[4][8]

Age groups in the 2nd to 5th decade are usually affected, but isolated reports have been seen even in older individuals. Although there is no evidence of genetic inheritance of PMCD, a few authors have reported high astigmatism seen in family members of these patients.[9] There also seems to be a co-existence of PMCD and keratoconus in about 10% of patients.

Histopathology

Histopathological studies report an absent or irregular Bowman's membrane with breaks. An increase in stromal mucopolysaccharides and stromal thinning has been reported. Descemet's membrane might show folds occasionally. Electron microscopic studies have shown the presence of irregularly arranged stromal collagen bundles along with the presence of extracellular, granular electron-dense deposits. These electron-dense areas were found to be islands of fibrous long spacing (FLS) collagen with a 100 to 110 nm periodicity in a sea of normally spaced collagen bundles (60 to 64 nm periodicity). Similar histopathological patterns have been observed in cases of advanced keratoconus with severe thinning.[7]

History and Physical

Most commonly, a gradual, progressive diminution in vision or longstanding poor visual quality is the presenting feature of these patients. But best-corrected visual acuity becomes poor only in advanced stages. On evaluation, high irregular, against-the-rule astigmatism is commonly found.[1] The flattening in the vertical meridian is due to tissue loss and a thin stroma in a crescentic pattern. The steepening and ectasia occur at the junction of affected and unaffected tissue, leading to the typical high cylindrical loop. The high against-the-rule astigmatism stems from a paradoxical steepening at 90 degrees. Rarely on presentation, these patients can report a sudden, painful red eye with watering accompanied by a sudden drop in vision and photophobia due to acute hydrops and/or spontaneous corneal perforation.

Examination reveals stromal thinning of the periphery of the cornea, extending mostly from 4 o'clock to 8 o'clock, in a crescent shape, and has a slow and progressive development. Usually, the entire cornea is clear, and no vascularization, Fleischer ring, lipid deposits, or changes in corneal sensitivity are observed. As opposed to keratoconus, the area of maximal ectasia lies above the thinnest location giving the cornea an appearance of a beer belly when visualized from the side. Between the thinned out band and the limbus, there is usually a 1 to 2 mm wide area of uninvolved, normal cornea.[7][10] Concentric Descemet's folds like Vogt's striae have been seen in a few patients.[11] The presence of Munson or Rizzuti signs may be variable but is not characteristically associated with PMCD.

Although PMCD is usually found bilaterally, unilateral cases have also been reported.[12][13][14] Atypical locations in the form of superior, nasal, and temporal PMCD have also been documented in the literature.[15][16][17][18][19] In superior PMCD, a narrow band of 1 to 2 mm (ectasia below thinnest location), located around 1.5 to 2 mm below the superior limbus extending from the 10 o'clock to the 2 o'clock position is seen.

Evaluation

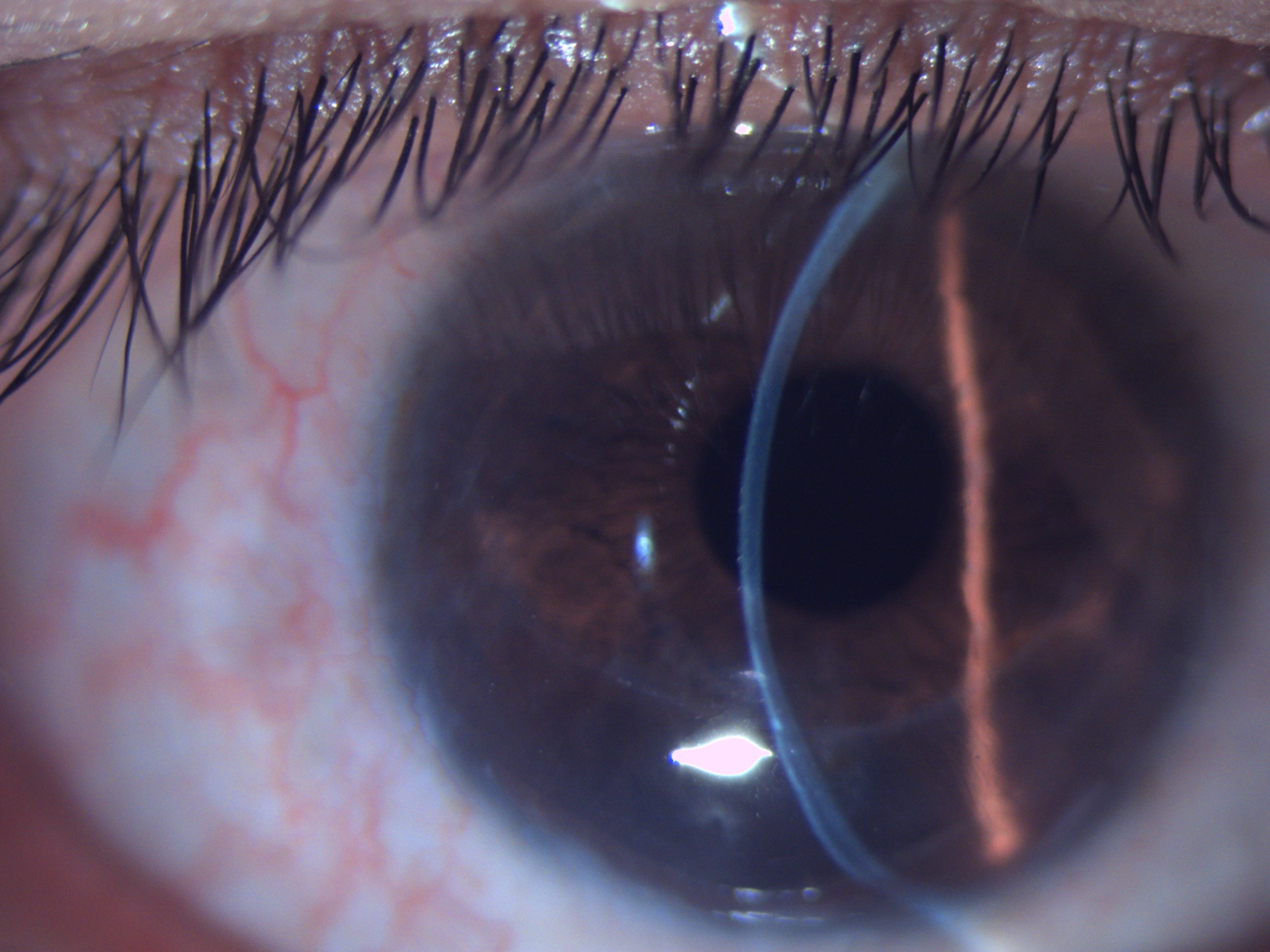

The gold standard investigation for PMCD and other corneal ectasias is corneal topography. Topography machines have evolved from the older videokeratoscopy to new generation slit scanning and Scheimpflug imaging technologies. With a better evaluation of posterior corneal morphology, these diagnostic modalities have made early detection of ectatic disorders possible. In PMCD, inferior peripheral steepening extending into the mid-peripheral, inferior oblique corneal meridians results in a characteristic “crab-claw,” “butterfly,” or “kissing doves” appearance on the curvature/keratometric map on topography.[6][20][21]

The elevation maps typically show a hot spot (area of elevation) in the inferior periphery. However, sometimes, these can also be observed in advanced keratoconus; hence emphasis must be laid on clinical and pachymetric correlation for a definitive diagnosis. The pachymetry of PMCD patients shows a reversal from normal i.e., thinner in the periphery (usually inferior) and thicker in the center.

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography and Scheimpflug images might help to assess the thinnest location in cases where points of minimum thickness cannot be picked up by topography.

Treatment / Management

Management modalities can be classified as conservative/visual rehabilitative treatment and surgical treatment. In general, the treatment of PMCD is difficult due to advanced thinning and severe protrusion. Still, many patients with early and moderate disease can be rehabilitated visually with spectacles or contact lenses, the latter being superior for correction of very high cylinders.

The fitting of contact lenses in PMCD is, in general, more challenging than other ectatic diseases due to the large area of inferior protrusion and inability of the contact lens to ‘sit on the cone.’ Routine rigid gas permeable (RGP) lenses often pose decentration challenges. Large diameter RGP lenses may be particularly useful. Other contact lenses like hybrid lenses with a soft skirt, semi scleral and scleral lenses, toric lenses, and prosthetic replacement of ocular surface ecosystem (PROSE) lenses have been found to be useful.[22][23][24][25]

Surgical treatment comprises intracorneal ring segments (ICRS), collagen cross-linking (CXL), and partial and total corneal replacement procedures. Intracorneal ring segments are polymethyl methacrylate segments that work on the principle of addition of extra tissue in the peripheral tissue, thereby creating steeping in the periphery and flattening in the center. However, ICRS implantation is limited to specific corneal requirements like corneal thickness >450 micrometers; hence its use in PMCD is only limited to early/moderate cases. Further complications like extrusion, neovascularization along the segment, channel deposits, segment migration, epithelial ingrowth, and corneal melts limit their usage.[26]

CXL acts on the principle of causing photopolymerization of disulfide bonds in corneal collagen with the help of riboflavin and ultraviolet A (UV-A) radiation. Its role in halting the progression of keratoconus is well established. However, only a few studies have mentioned its role in PMCD because of challenges associated with the decentration of the UV-A beam to achieve the required effect at the peripheral cornea and propensity of limbal tissue damage.[27][28][29]

Corneal transplant procedures for PMCD include full-thickness penetrating keratoplasty with a large or eccentric graft. In spite of it being surgically less challenging, the potential risk of rejection because of the vicinity to limbal vasculature and damage to limbal epithelial cells makes it a less viable option.[30]

“Tuck in” lamellar keratoplasty (TILK) is a unique type of lamellar keratoplasty done for advanced ectasia disorders. It is comprised of a central button of anterior lamellar keratoplasty with an added intrastromal tuck of the peripheral flange of donor tissue into the host. Very good results were observed with TILK in patients with PMCD, with its inherent advantages of doing away with the challenges of large grafts.[31]

Other promising procedures include crescentic lamellar keratoplasty, combined central penetrating keratoplasty, peripheral crescentic lamellar keratoplasty, intrastromal lamellar keratoplasty, lamellar or full-thickness crescentic wedge resection, and epikeratoplasty.[32][33][34][35][36] Nevertheless, there are many potential risks of lamellar procedures, including the risk of perforation during lamellar dissection through the thinnest portion, epithelial ingrowth, wrinkles in lamellar graft, double chamber formation, graft dehiscence, stromal rejection, and interface problems.

Differential Diagnosis

PMCD is most commonly misdiagnosed as keratoconus. Involvement of the central two-thirds of the cornea, ectasia, and thinning at a common location with the apex of cone shifting inferiorly along with the presence of signs like scissoring reflex, Vogt striae, Fleischer ring, and presence of asymmetric bow tie with a skewed radial axis on topography can clinch the diagnosis of keratoconus.[37][38]

Another commonly confused entity is keratoglobus, which involves corneal thinning ranging from limbus to limbus. Hydrops may also be associated with keratoglobus.[39][40]

A similar picture has been seen in other ectasias, such as Terrien's marginal corneal degeneration. However, the steepening of the inferior periphery with extension to the horizontal, oblique meridians are believed to be characteristic of PMCD.

Furrow degeneration is another peripheral thinning disorder seen in the older age groups. Both furrow degeneration and PMCD are non-inflammatory in etiology and are not accompanied by corneal vascularization, lipid deposits, or scarring. The circumferential thinning seen in-furrow degeneration is limited to the lucid interval between the limbus and arcus senilis.[41]

Sometimes inflammatory disorders like peripheral ulcerative keratitis and early Mooren's ulcer can be mistaken for PMCD. The presence of an associated painful congested eye and vascularization can differentiate between the two.

Prognosis

PMCD progresses slowly over the years, and hence sometimes patients seek intervention relatively late. Overall, most patients require visual rehabilitation in the early stages and corneal transplant procedures in advanced stages. Though not many studies have reported on the prognosis of PMCD, the results of CXL and ICRS have been satisfactory in early to moderate cases. Data is inadequate to comment on the exact numbers requiring corneal transplantation in the course of the disease. TILK has particularly shown good success in advanced cases.

Complications

Complications, although rare, can range from stress lines to corneal hydrops and spontaneous corneal perforations. Some cases might develop posterior stromal scarring. Refractive surgery in these patients due to a failure to recognize the pathology can have deleterious consequences.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients with PMCD, whether or not surgically intervened, will require lifelong follow-up and visual care. There have been reports of early suture loosening and rejections in post keratoplasty cases. So postoperatively, these patients need to be closely followed up for almost a year. Even post-surgery, these patients will require glasses for complete visual rehabilitation.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The exact etiology of PMCD is unknown, and hence the disease cannot be prevented. However, avoidance of frequent eye rubbing (implicated by some in the etiology) should be recommended. Patients with advanced disease and severe corneal thinning should be advised to protect their eyes from trauma as it could lead to perforation. These patients should be counseled to get timely ophthalmic examinations done to document progression.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

PMCD is best managed by an interprofessional team approach. Patients with vision problems such as frequent changes of their glasses and high against the rule astigmatism should be particularly screened by referral to an optician, ophthalmic nurse, and ophthalmologist. A simple slit-lamp examination, along with topography, can clinch the diagnosis. Today, several treatments are available for PMCD. Timely detection and appropriate visual rehabilitation can increase the quality of life of these patients. There is a link between collagen vascular disorders and corneal ectatic disorders; thus, appropriate medical referral for a systemic checkup is mandatory in suspicious cases.